We are at the end of a global crisis. The outbreak of COVID-19 has caused detrimental and long-lasting socio-economic tremors to the world, with more than 1.5 million people have lost their lives (UN, 2020). The pandemic has also tapered the global economy by an unpleasant 4.3 per cent and due to the downturn in the global financial market, millions of livelihoods remain at risk (IMF, 2020). Much uncertainty remains in dealing with the rising poverty rates, food crises, and international blockades.

According to a report by World Bank, about 150 million people globally will be in extreme poverty by 2021 due to the pandemic and global recession, 47 million of whom will be women and girls resulting in the total number of females living on USD 1.90 or less, to 435 million (World Bank, 2020). As the crisis continues to unfold, it remains a major threat to global food security. As per the estimates of the WFP, by the end of 2020, a further 137 million people will fall into the loop of acute food insecurity, mainly impacting the poor and vulnerable apart from the surviving 690 million people who were chronically food insecure afore the stroke of the COVID-19 crisis (WFP, 2020). Elevated food insecurity and malnutrition approximations reflect the multiplier effect of the epidemic. Estimations reveal that the impact of Covid-19 is stern on children and lack of vigilance can cause an additional 6.7 million children to suffer from child wasting (The Lancet, 2020). About 370 million school-age children across 143 countries missed out on their school plus provided school meal due to pandemic which might be their only nutritious food for every day triggering more than 10 thousand additional child deaths each month in the first 12 months of the pandemic (WFP, 2020). Supply chain disruptions and trade restrictions due to COVID-19 have created strong food price tensions and food security risks in many countries. However, the dynamic concept of food security does not necessarily imply that a nation has to be self-sufficient in food availability, rather it suggests that sufficient and nutritious food must be available through sharing and balance.

India, being the second most populated country in the world, is facing a parallel challenge. Over the past two decades, India has emerged as one of the world’s fastestgrowing economies; however, the pandemic has weakened its economic growth. The reduced domestic demand and altered consumption have induced its trade market to turn inward and further plummet. This is visible through raised tariffs and suspended trade agreements, although, after envisaging its inclusive economic impact, the government is gradually rolling out the restrictions.

However, the crisis has exposed the susceptibilities of the cur Agri-food system like shortages, distress sale, and sharp price hikes of import-oriented commodities. The threat of contagion has evidently shifted the food demand towards more healthy dietary choices appended with restricted outings, reduced restaurant traffic, and augmented electronic deliveries. Changing geopolitics across the region has created a huge comparative advantage in agriculture production for a country like India which has been already standing a decent grip on exports of grains, vegetables, spices, dairy, etc. After six months of economic turbulence, Indian exports have increased by a staggering 5.37% in September 2020 and overall food exports have also risen 27% since March 2020 (Hindu, 2020). Likewise, as China-Australia trade has fizzled out recently, India-Australia trade has seen better prospects. A nation with mounting population growth, rise in household incomes, and urbanisation, India stands as an attractive opportunity in trade. Though the global economic downturn has adversely affected food consumption demand (mainly high-value products) there is a strong chance of a blooming two-way trade between India and Australia

The relationship between India and Australia prospered in times of the coronavirus when Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Hon’ble Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi, participated in the Australia-India Leaders’ Virtual Summit on 4 June 2020. At this summit, the prime ministers of both nations raised the bar of the Bilateral Strategic Partnership which concluded in 2009 to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP). The Comprehensive Strategic Partnership boosted the agenda of bilateral trade and economic relationship and through the CSP, both countries have committed to working together across a range of areas (DFAT, 2020).

India and Australia signed the following agreements in June 2020:

- Joint Statement on a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership between the Republic of India and Australia

- Joint Declaration on a Shared Vision for Maritime Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific

- Framework Arrangement on Cyber and Cyber-Enabled Critical Technologies Cooperation

- Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on Cooperation in the field of Mining and Processing of Critical and Strategic Minerals

- Arrangement Concerning Mutual Logistics Support

- Implementing Arrangement concerning Cooperation in Defence Science and Technology to the MoU on Defence Cooperation

- MoU on Cooperation in the field of Public Administration and Governance Reforms

- MoU on Cooperation in Vocational Education and Training MoU on Water Resources Management

In terms of food security, Australia holds the 12th ranking in the world (GFSI, 2019) and is a significant exporter of agricultural products. Australia has diverse agriculture, fisheries, and forestry that produce a wide range of crops and livestock, allowing it to export around 70% of its total production. Over the last 20 years, the total value of agriculture, fisheries, and forestry exports has grown considerably. Livestock and meat exports were the fastest-growing export items (99 %) followed by forestry products (54%) and fruit and vegetables (37%). Australia accounted for 11% of goods and services exports in 2018–19. For Australian agriculture, Asia is the fastest-growing export region witnessing an overall rise of 86% over the last 20 years and taking up 60% of the total value of Australian agriculture exports in 2019. There has been substantial growth in global agricultural demand due to the growing world population and elevated earnings (Jackson et. al, 2020).

The bilateral relationship between Australia and India has been blooming over the past few years and in 2020, the two nations established themselves as a foundation of the Indo Pacific – politically, economically, and militarily. Between 2013 – 16, Australian exports to India doubled from $11 billion to $22 billion (DFAT, 2020). In 2018-19, India was the fifth largest export market to Australian exports and the eighth largest trading partner. Over the next 20 years, it is estimate that India’s fast-growing economy will trigger increased demand for Australian goods and services. The relationship will generate fresh opportunities for Australian agribusinesses, education providers, resources companies, and the tourism industry in India. However, it is worthy to note that the free trade agreement between India and Australia is subject to post-COVID-19 distortions, and in June 2020, there has already been a sharp decline in Australian exports to India. Yet, the Australian Government is committed to transforming Australia’s economic partnership with India between now and 2035. Its goals include lifting India into its top three export markets and making India the third-largest destination in Asia for outward investment. Moreover, the topical strategies of Australia and India in response to the Chinese Communist Party’s decisiveness in the COVID-19 crisis have reinforced mutual perceptions of each other’s reliability.

Opportunities for Australian agriculture and dairy products in India

While there is a myriad of reasons why India makes for an attractive opportunity for Australian agriculture exporters, the current and projected population of India coupled with its rising income growth are the main drivers. The top six trade products exported to India are products that are exported by Australia, including cotton, fruits, nuts, pulses, unrefined sugar, and wool. Moreover, ‘clean, green’ foods from Australia hold an excellent class reputation in the Indian market. However, organic exporters form India encounter hurdles in market entry owing to a lack of recognition of Australia’s organic standards (Varghese, 2018)

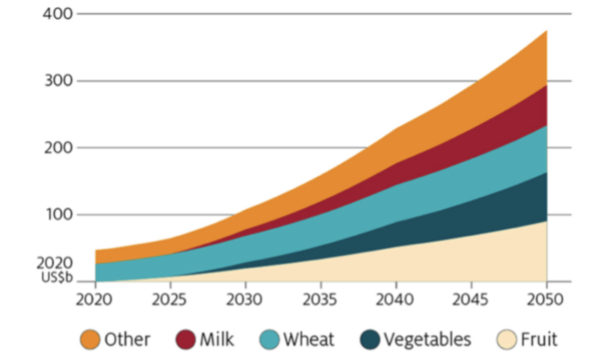

Figure 1: Exports to India have strong long-term demand growth prospects (Source: Hamshere et al. 2014)

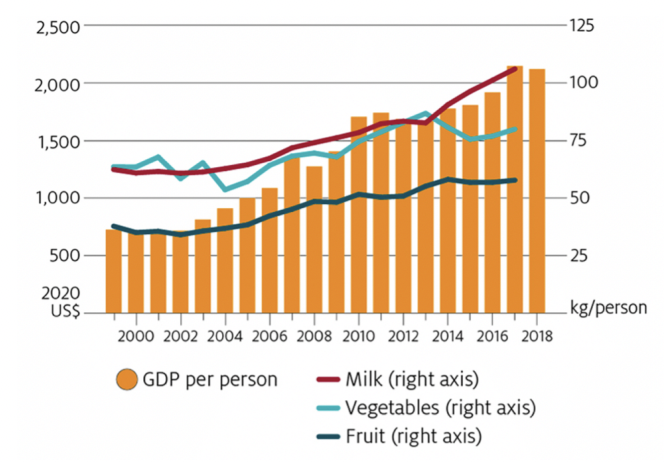

While Australia’s main agriculture exports are pulses and grains, due to recent economic and trade strategies, the fresh prospect of trade is expanding produces. The projected value of total agriculture consumption in India is going to double by 2050. Dairy, fruit and vegetables contribute to the majority of this increase. India’s per-person consumption of milk increased by nearly 40% between 2009 and 2018, and perperson consumption of fruit by 21% (ATIC, 2020). Urbanisation is a significant element in determining the quality and quantity of food demand, as urban people usually have higher incomes and can access a wider range of dietary products. Over the last decade, the Indian population has shown an unparalleled rise in the urban settlement, boosting the demand the value-added products and creating a thriving opportunity for Australia’s raw commodities exports (Varghese 2018).

Figure 2: Food consumption per person has risen with average income (Source: IMF 2019, FAO 2020)

Indian food-processing corporations are looking for partners to deliver high-quality products. Lately, there has been a relaxation of wholesale market regulations and agriculture policy reforms are creating excellent opportunities in research, logistics, and warehousing. India welcomes Australian Agtech, especially grain-tech (ATIC, 2020). India and Australia are strengthening bonds through the trade of fruits. The export of pomegranates to Australia has been made following an import risk assessment and it is an important step in the bilateral association. According to Barry O’Farrell (the Australian High Commissioner to India) – “While Australia already produces pomegranates, India is well placed as one of the world’s largest pomegranate producers to meet shortfalls in the Australian markets.” Until now, India only exported mangoes and table grapes to Australia. It is hoped that this will open the door for many other fruits to be exported, as long as biosecurity conditions in Australia are met. India exported fruits and vegetables worth Rs 9,182 crores which consisted of fruits worth Rs 4,832 crores and vegetables worth Rs 4,350 crores during 2019-20, according to government figures (Nayar, 2020).

In terms of horticulture, India is realizing the value of good nutrition and is developing a taste for imported fruits and vegetables. It has embarked on significant year-round demand for fresh fruits and vegetables, with the total food imports tripling in the last decade from A$2.4 billion in 2009 to A$7.5 billion in 2019 (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, An Indian Economic Strategy to 2035, Agribusiness Sector, 2018). Australian exporters are attractive because they are faster (21-26 days) in delivering food items to the Indian market than their competitors in the USA (40 days). Australian exporters are also working with top groups to amass exports of stone fruits like peaches, plums, and cherries. The growing e-commerce network is expanding the demand for imported fruit and is creating profound ways of distribution. For non-veg food items, Lamb meat is more popular in Indian cuisine as beef is not consumed. 4 Australian barley has a big advantage due to the strong appreciation of its quality in the Indian market. Overall, Australia has great scope in India, compared to its partners such as Argentina and the European Union (ATIC, 2020).

The Government of India aims to ensure food security for all with optimum food sufficiency and income support for farmers. Despite India’s focus on domestic production and self-sufficiency, the aperture within anticipated demand and supply might grow out to 2035. The agriculture growth in India is unevenly distributed and deficiencies to fulfil concentrated demand for high-value products like proteins, variety of fruits, and packaged goods, etc., will hinder the objective of gaining autonomy. Australia is riding a long lane of opportunities in contributing to the agribusiness space of India. Australia, utilizing its technical expertise, can offer its agricultural science experience to recuperate the status of food security in India by tapping into the growing demand for staple and high-value products in a sustainable and productive way. For Australia, trade potential lies in the supply of commodities that are deficits in production like pulses, grains, horticulture, oilseeds, and likewise, in the vaue-added products, and for providing specialized services to Indian Government, institutions, and farmers. There is also a significant demand for Australian dairy products in India, such as milk powder, fats, oils, casein, butter, whey, and lactose. Despite tariffs and trade regulations, demand for cheese and cream in the Indian market is also surging. As a significant section of India is leaning towards more healthy and conscious food choices, there stands a greater scope for Australian value-added dairy products like fortified milk or A2 milk. Australian skimmed milk powder exports are continuing to grow and are competing with local distributors.

Australia-India food trade is also marred by challenges. There are high average tariffs for pulses and grains. Although there is an advancement in logistics, there is still a lack of a cold chain. Quality is also an issue: Australian exports are competing with domestic suppliers and American and European Union producers; therefore, the products should be of high quality.

The full paper can be downloaded here.